Running a crystal-growing competition

During IYCr2014 the IUCr wants to stimulate as many countries as possible to organize a regional or national crystal growing competition. To facilitate this, the IUCr offers all possible support for newcomers in the form of a time line, protocols, suggestions for judging and prize awarding etc. Successful current competitions can act as buddy or mentor for new initiatives.

The following material is also available in pdf format. Click here to download the brochure.

This page also provides links to the class 1972 pamphlet Crystals - a handbook for school teachers by Elizabeth Wood, in a number of languages.

We are grateful for most of the information in these pages to the organizers of the Canadian, Belgian, Singapore, Spanish and Australian Crystal Growing Competitions.

Final Event of the 2013 competition in Spain

Scenario for a successful competition

For many years crystal growing competitions have been run successfully in a number of countries. With the help of the IUCr the organizers of these competitions want to share their experience with future organizers. The IYCr in 2014 provides perfect timing to start a new competition in your region or country. We present you with a scenario to do this and offer support in case of questions.

Things to decide before...

- who can participate (age limit? different categories? regional or national)

- how to register

- material to crystallize (sponsoring? how delivered? safety)

- time period (depending on the school year)

- judging on single crystal quality only, or together with other items (poster, log book, ...) and who will do the judging?

The ideal timeline

![[competition timeline]](https://iycr2014.org/__data/assets/image/0017/83204/timeline.png)

- Start your registration early enough, preferably done by the teacher with a electronic registration module.

- Provide two weeks for shipping and delivery of the product.

- Before starting the experimental work the teacher should give some extra background for the pupils (about crystals, symmetry, solubility, crystal growth, ...)

- Ideally 4-5 weeks are necessary to grow nice crystals.

- Ask the participants to keep a part of the wire at the crystal and to attach a label containing name and age of participants, school and weight of the crystal.

- Give each crystal a unique number for the scoring.

- Organize a prize awarding ceremony at a central location.

Some additional tips

Announcing your competition

Use email lists of chemistry, physics and biology teachers to announce your competition. Be present at events for teachers or present your activity in publications especially for teachers.

Individual or group work?

Growing a beautiful crystal takes time and an almost daily follow-up. For this reason it is better to divide the class into several groups of 4-5 pupils. Each group has then its own crystallization set-up and pupils can do the follow-up by rotation.

Local coordinators

Teachers and pupils may have a lot of questions during the competition. To prevent the mailbox of the coordinator from being overloaded, it is very practical to work with local coordinators who are the contacts for a certain region. Together all local coordinators can act as jury!

Prize awarding ceremony

Credit: Singapore National Crystal Growing Challenge

It is very important that the hard work of the pupils is recognized! In case only the quality of the submitted crystals is used, the proposed formula will work fine. When other items are combined, the ceremony should be preceded by a crystal fair where pupils present poster and logbooks and exhibit their crystals. Think of different categories of winners (age, longest crystal, heaviest crystal, best school ...). Use trophies (e.g. natural single crystals), medals or certificates for winners and participants. Combine the ceremony with a lecture on a crystallographic topic or show a video on crystals. Provide a press release.

Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt

Teacher formation

It is important to provide enough background information for the teachers. In fact you should convince teachers to participate with their class, and they should motivate their pupils in their turn. Put some background information about crystals, symmetry and crystal growth on your website or provide links to existing material (e.g. www.xtal.iqf.csic.es/Cristalografia/index-en.html). Organize a workshop for teachers!

And the costs ...?

Provided that you can find a sponsor for the starting material (e.g. a supplier of chemicals) the costs related to the organization of a crystal growing competition are rather low: development of website, translation, prize awarding ceremony including trophies and prizes. Unfortunately IUCr cannot provide financial support. For the prizes, sponsorship is also probable. Trophies can be home-made: buy some interesting natural single crystals of pyrite, quartz, fluorite, calcite or bi-terminated black tourmaline and glue them on to a support.

How to Grow Crystals

The idea is to grow a single crystal, not a bunch of crystals. You will first need to grow a small perfect crystal, your seed crystal, around which you will later grow a large crystal. It is therefore essential to avoid excessive rapid growth, which encourages the formation of multiple crystals instead of a single crystal.

What You Need...

- Substance to be crystallized

- Distilled or demineralized water

- A small wood rod, popsicle or sate stick

- A shallow dish (e.g. Petri dish)

- Thermometer

- Balance

- Plastic or glass container

- Heating plate

- Beaker of 2 to 4 litres volume

- Fishing line (1 to 2 kg strength)

- Superglue

- Styrofoam box or picnic cooler

- A magnifying glass

Important Things to Know in Advance!

- How much substance you have to work with, which you can determine by weighing it on a balance.

- The solubility of the substance in water at room temperature, which you can obtain from a chemistry reference book.

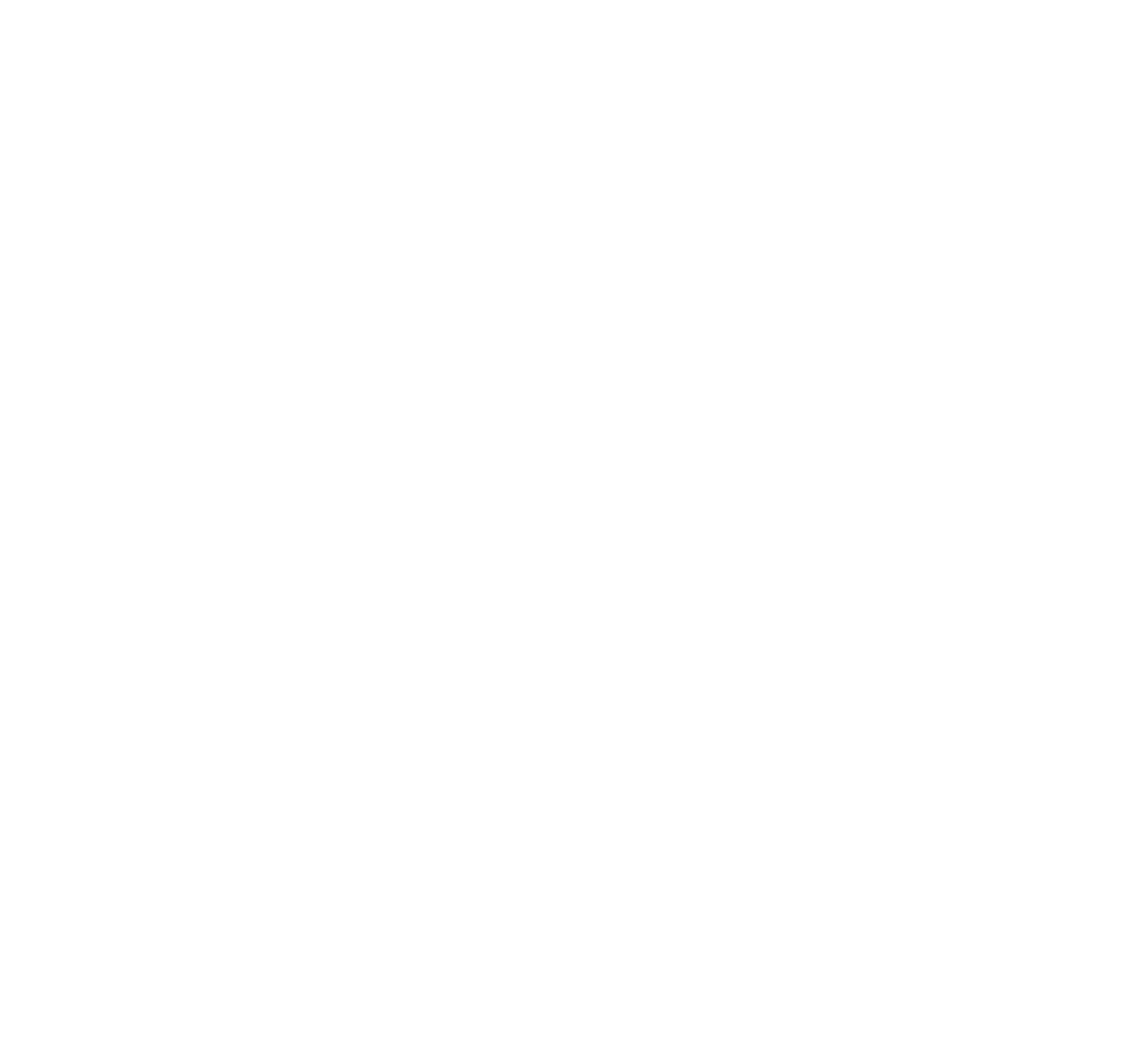

- It would also be useful to know the solubility of the substance at elevated temperatures, which is information that may also be available in a reference book such as Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Figure 1 shows the solubility of alum as function of the temperature.

Of course, you need to make a careful assessment of any risk or safety precautions associated with the material you plan to use. For example,

- check the safety data sheet supplied with any chemicals;

- ensure that children are aware of the dangers of hot plates, or of mounting materials such as superglue;

- use safety glassware and other appropriate laboratory equipment;

- provide lab coats, gloves and safety goggles as appropriate.

The protocol!

First Stage: Grow a Seed Crystal

- Warm about 50 mL of water in a glass container.

- Dissolve a quantity of the substance to produce a saturated solution at the elevated temperature.

- Pour the warm solution into a shallow dish.

- Allow the solution to cool to room temperature.

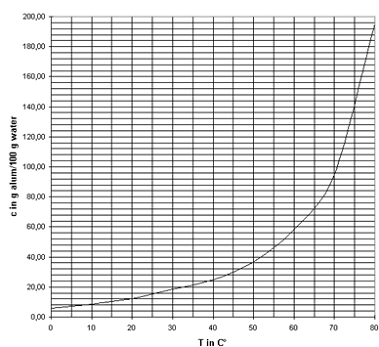

- After a day or so, small crystals should begin to form as in Figure 2.

- Remove some of the crystals.

- With a magnifying glass select a beautiful and transparent small crystal. This will be your seed crystal. Weigh the crystal.

Figure 2. Seed crystals of alum. (Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt)

Second Stage: Grow a Large, Single Crystal

- Glue the seed crystal at the end of a piece of fishing line by using superglue (be careful not to glue your fingers together!).

- Check with the magnifier that the seed crystal is well-fixed to the line.

To grow your large, single crystal, you will need a supersaturated solution.

The amounts of substance and water to be used will depend upon the solubility at room and elevated temperatures. You may have to determine the proper proportions by trial and error (just like the first scientists did).

- Place about double the amount of substance that would normally dissolve in a certain volume of water at room temperature into that volume of water. (e.g. If 30 g of X dissolves in 100 mL of water at room temperature, place 60 g of X in 100 mL of water.) Adjust the proportions depending upon how much material you have. Use clean glassware.

- Stir the mixture until it appears that no more will go into solution.

- Continue stirring the mixture while gently warming the solution.

- Once all of the substance has gone into solution, remove the container from the heat.

- Allow the solution to cool to room temperature.

- You now have a supersaturated solution. Allow to cool to room temperature.

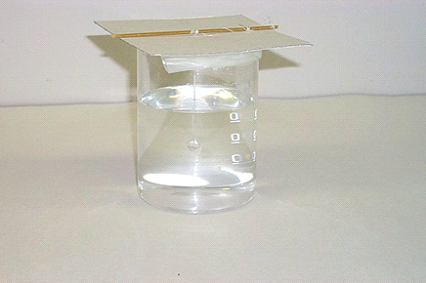

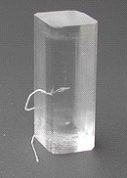

- Carefully suspend your seed crystal from the stick into the cold supersaturated solution in the middle of the container with supersaturated solution (Figure 3).

- Cover the container in which the crystal is growing with plastic wrap, aluminum foil or a piece of cardboard in order to keep out dust, and reduce temperature fluctuations.

Figure 3. Seed crystal of alum suspended in saturated solution. (Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt)

Figure 4. Styrofoam or isomo box.

- Observe the crystal growth. Depending upon the substance, the degree of supersaturation and the temperature, this may take several days before the growth slows down and stops.

- Resupersaturate the solution. This may need to be done on a daily basis, especially when the crystal gets larger. But first, remove the crystal.

- Each time the solution is saturated, it is a good idea to ‘clean’ the monocrystal surface, by

-

- making sure the crystal is dry;

- not touching the crystal with your fingers (hold only by the suspending line if possible);

- removing any ‘bumps’ on the surface due to extra growth;

- removing any small crystals from the line.

- Resuspend the crystal back into the newly supersaturated solution.

- Repeat the previous steps as needed.

Some FAQ's...

Why does the crystal stop growing?

A crystal will only grow when the surrounding solution is supersaturated with solute. When the solution is exactly saturated, no more material will be deposited on the crystal. (This may not be entirely true. Some may be deposited, however an equal amount will leave the crystal surface to go back into solution. We call this an equilibrium condition.)

Why did my crystal shrink/disappear?

If your crystal shrank or disappeared, it was because the surrounding solution became undersaturated and the crystal material went back into solution. Undersaturation may occur when the temperature of a saturated solution increases, even by only a few degrees, depending upon the solute. (This is why temperature control is so important.)

How do I get crystal growth restarted?

Make the solution again supersaturated!

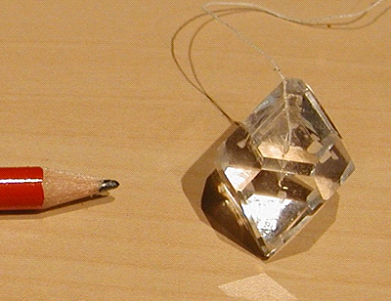

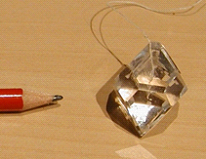

Help, my crystal loses its transparency!

When removing the crystal from the solution, clean it very quickly in water to rinse the thin layer of solution on the crystal surface away. Otherwise this thin layer would leave an amorphous precipitate on the surface after evaporation. This will decrease the transparency of the crystal, and you will not be able to harvest a perfect transparent crystal as in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Transparent alum crystal. (Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt)

What is the difference between an undersaturared, saturated and supersaturated solution?

In recrystallization, one tries to prepare a solution that is supersaturated with respect to the solute (the material you want to crystallize). There are several ways to do this.

One is to heat the solvent, dissolve as much solute as you can (said to be a "saturated" solution at that temperature), and then let it cool. At this point, all the solute remains in solution, which now contains more solute at that temperature than it normally would (and is said to be "supersaturated").

This situation is somewhat unstable. If you now suspend a solid material in the solution, the "extra" solute will tend to come out of solution and grow around the solid. Particles of dust can cause this to occur. However this growth will be uncontrolled and should be avoided (thus the recrystallization beaker should be covered). To get controlled growth, a "seed crystal", prepared from the solute should be suspended into the solution (Figure 6).

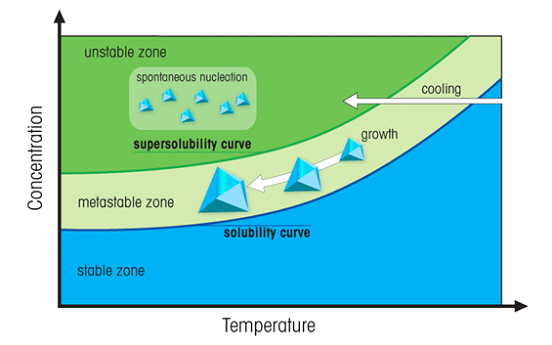

Figure 6. The region above the solubility curve is the called "supersaturated". In the unstable zone (green) spontaneous nucleation occurs. A crystal suspended in the metastable zone will grow further.

The supersaturation method works when the solute is more soluble in hot solvent than cold. This is usually the case, but there are exceptions. For example, the solubility of table salt (sodium chloride) is about the same whether the water is hot or cold.

Can I prepare a supersaturated solution in a different way?

A second way to get supersaturation is to start with a saturated solution and let the solvent evaporate. This will be a slower process. A third method is given below:

- Select an appropriate volume of water.

- Warm this water to about 15–20 deg above room temperature.

- Add some of your substance to the warm water and stir the mixture to dissolve completely.

- Continue adding substance and stirring until there is a little material that won’t dissolve.

- Warm the mixture a bit more until the remaining material goes into solution.

- Once all of the substance has gone into solution, remove the container from the heat.

- Allow the solution to cool to room temperature.

- You now have a supersaturated solution.

I am a perfectionist, what can I do additionally?

To get improved symmetry and size, slowly rotate the growing monocrystal (1 to 4 rotations per day). An electric motor with 1 to 4 daily rotations might be difficult to find (consider one from an old humidity drum-register or other apparatus). This option becomes useful only when a monocrystal gets rather big. You can also place the beaker into a thermostated bath set to a few degrees above room temperature.

Slow or fast growing, what is the best?

The rate at which crystallization occurs will affect crystal quality. The more supersaturated a solution is, the faster growth may be. Usually, the best crystals are the ones that grow slowly.

What is the effect of impurities?

Once you have mastered the crystal growth, you may be interested in trying to grow single crystals in the presence of introduced ‘impurities". These impurities may give different crystal colours or shapes.

Does this method also work for proteins?

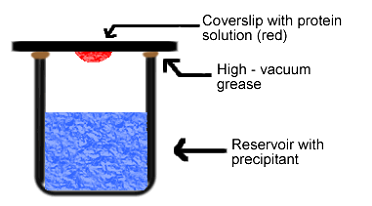

No, it is not possible to make a supersaturated protein solution by dissolving protein into a hot solvent. The protein will denaturate and loose its regular folded structure. A special set-up is needed here. In the hanging drop method (Figure 7) for example, a droplet containing protein, buffer and precipitant is hanging above a larger reservoir containing buffer and precipitant in a higher concentration. As water evaporates from the droplet it will transfer to the reservoir where it is bound to the precipitant. During this process the protein is concentrated. Once supersaturation is reached, nucleation and crystal growth is starting.

How are the single crystals judged?

A single crystal can be judged on the basis of its quality or a combination of mass and quality. Judging criteria are given below. You can provide different categories, e.g. according to age, best quality, best school, longest crystal etc...

Judging criteria

Credit: picture by Dirk Poelman

The quality is judged by experts who will rank the crystals on a scale of 0 to 10. A score of 10 will be given to a perfect gem-quality crystal that fits the ideal crystal structure known for the chemical.

- The crystal is weighed, and the mass M recorded. It is possible to require a minimum mass, e.g. the crystal must be a minimum of 0.5 g to be eligible for judging.

- The quality of the crystal is judged on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 representing a perfect crystal. The following factors will be considered in judging quality:

- match/mismatch with crystal type (out of 2)

- presence/absence of occlusions (out of 2)

- intact/broken edges (out of 2)

- well formed/misformed faces (out of 2)

- clarity/muddiness (out of 2)

Total Observed Quality Q = x.xx (out of 10)

- The Total Score is then determined as follows:

Total Score = [log (M+1)] x Q

The logarithm of the mass is chosen so that large poor quality crystals don’t swamp out smaller good quality crystals.

The value 1 is added to the mass so that crystals weighing less than 1 g get a positive score.

Overall score

Instead of using the Total Score to indicate the winning crystals, one can also take the amount of starting material into account.

A 100 per cent yield crystal made from 100 g (Mt) that scores a perfect 10 on quality (Qt) would get a theoretical maximum of:

[log (100+1)] x 10 = 20.01

The actual score can also be expressed as a percentage of the maximum. The crystal with the highest Overall Score is then the winning crystal.

100 x {[log (M+1)] x Q} / {[log (Mt+1)] x Qt} = Overall Score %

For example, the best overall crystal in the Canadian 2001 contest with 150 g starting material weighed 46.53 g and had a quality of 8.65. Its overall score was:

100 x {[log (46.53+1)] x 8.65} / {[log (150+1)] x 10} = 66.6%

This score is nearly an absolute score that could be used to judge different types of crystals grown from differing amounts of starting material.

Compounds to crystallize

Potassium Aluminium Sulfate

Also known as "Alum" or "Potassium Alum" and has the chemical formula of KAl(SO4)2.12H2O, gives transparent octahedral crystals. Solubility: 118 g/L (20°C, water).

Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt

Disodium Tetraborate

Also known as "Borax" and has the chemical formula of Na2B4O7.10H2O, gives transparent crystals. Solubility: 27 g/L (anhydrous, 20°C, water).

Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt

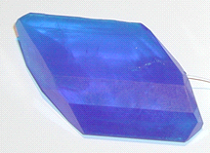

Copper(II) Sulfate Pentahydrate

Has the chemical formula of CuSO4.5H2O, gives blue crystals. Solubility: 390 g/L (anhydrous, 20°C, water).

Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt

Monopotassium phosphate

Also know as "KDP", has the chemical formula of KH2PO4, gives transparent long crystals. Solubility: 22 g/100 mL (anhydrous, 25°C, water).

Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt

Ammonium Magnesium Sulfate Hexahydrate

The crystallization is started from ammonium sulfate and magnesium sulfate. Dissolve at room temperature equivalent amounts of both salts in water (e.g. 0.4 mol of both compounds in 45-48 mL water). Stir until everything is dissolved. Now make the solution supersaturated by adding small amounts (2 to 5 gram) of both salts under gentle heating (max. 30-40 °C). Cover the beaker and allow to cool at room temperature. Now proceed with the crystal growth in the usual way.

Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt

Potassium Sodium Tartrate

Also know as "Seignette salt" or "Rochelle salt", has the chemical formula of KNaC4H4O6.4H2O, gives transparent long crystals. Solubility: 630 g/L (anhydrous, 20°C, water).

Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt

Ammonium Iron(II) Sulfate Hexahydrate

Also know as "Mohr's salt", has the chemical formula of (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2.6H2O, gives light green crystals. Solubility: 269 g/L (20°C, water).

Credit: picture by Luc Van Meervelt

Potassium Ferricyanide

Also known as "Red Prussiate of Potash" and has the chemical formula of K3Fe(CN)6. The recipe below gives red monoclinic crystals. Solubility: 464 g/L (20°C, water).

Dissolve 93 grams of potassium ferricyanide in 200 cc of warm water, cover the solution, and allow it to cool.

Credit: picture by Wayne Schmidt (http://www.waynethisandthat.com/crystals.htm)

Copper Acetate Monohydrate

Chemical formula: Cu(CH3COO)2.H2O. The recipe below gives blue-green monoclinic crystals. Solubility: 72 g/L (20°C, water).

Dissolve 20 grams of copper acetate monohydrate in 200 cc of hot water. If a scum of undissolved material persists, add a few drops of acetic acid and stir well. Cover this solution, and allow it to cool and stand for a few days; usually it will deposit crystals spontaneously.

Credit: picture by Coba Poncho

Calcium Copper Acetate Hexahydrate

Chemical Formula: CaCu(CH3COO)2.6H2O. The recipe below gives blue, tetragonal crystals.

Add 22.5 grams of powdered calcium oxide to 200 mL of water, pour into the mixture 48 grams of glacial acetic acid, and stir until the solution is clear. If there is a small insoluble residue, filter the solution. Dissolve separately 20 grams of copper acetate monohydrate in 150 cc of hot water. Mix the two solutions, cover the mixture, allow it to cool for a day. If it does not deposit crystals spontaneously, let a drop of the solution evaporate and scrape the resulting seeds into the bulk of the solution.

Sodium Chloride

Chemical Formula: NaCl. Also known as table salt. Solubility: 35.9 g/100 mL (20°C, water).

NaCl tends to form smaller crystals, or less well formed crystals because the solubility barely changes at all as a function of temperature; at 20°C, one can dissolve 35.9g of NaCl in 100g of water, and at 100°C, just 39.2g per 100g of water. The most appropriate method of growing sodium chloride crystals is therefore by evaporation of a saturated solution. Small (sub-millimetre) clear cubes with smooth faces will grow on the bottom of your glass dish or jar, or on any thread suspended in the jar. Larger crystals tend to develop hopper faces, or even more erratic growth habits. One interesting experiment to try is to see how the growth morphology changes if you add small quantities of other substances - a smidge of copper sulfate perhaps, K-alum, or sodium nitrate - to your saturated salt solution.

Sucrose

Chemical Formula: C12H22O11. Also known as saccharose or table sugar. Solubility: 211.5 g/100 mL (20°C, water).

Cane sugar produces great crystals without too much trouble, provided you can be patient. Dissolve ~500 grams of sugar per 100 mL of hot water, and leave to cool. The pale silvery-yellow solution is very viscous when supersaturated, and can take from a week to over a month to start producing crystals, depending on how big a jar you're using. Crystals shoot from smaller volumes of liquid quite quickly and can grow to a length of a few millimeters. Use these as seeds to grow much larger crystals. You can grow very pretty single crystals over a period of just a few weeks. Sucrose is slightly deliquescent; in other words, the crystals 'sweat' a bit. You'll find the crystals become slightly moist and sticky, even when you've dried them, particularly in a warm room.

Fructose

Chemical Formula: C6H12O6. Also known as fruit sugar. Solubility: 3750 g/L (20°C, water).

Solutions are made up in the same way as for cane sugar. As with sucrose, patience is everything. An 80 wt. % fructose solution, if unseeded, may take several weeks to start crystallising at room temperature; the first sign is the appearance of little flat squares floating on the surface of the solution. If you instead seed the solution with some of the tiny crystals from your original box, then what happens is that white 'blotches' - like cotton wool - appear in the liquid. These might be mistaken for bits of mould; in fact they are aggregates of very very fine hair-like crystals of fructose hemihydrate (C6H12O6 • ½H2O). The hemihydrate will also appear if you seed a concentrated solution kept in the fridge (at 1 - 4°C). Vigorous stirring of the solution breaks up the hemihydrate crystals and causes crystals of fructose dihydrate (C6H12O6 • 2H2O) to nucleate.

Potassium chromium sulfate

Chemical formula: KCr(SO4)2•12(H2O). Also known as chromium alum. Gives deep purple crystals. You can grow a clear alum layer around the purple crystals.

- The growing solution will consist of a chromium alum solution mixed with an ordinary alum solution. Make a chromium alum solution by mixing 60 g of potassium chromium sulfate in 100 ml water.

- In a separate container, prepare a saturated solution of ordinary alum by stirring alum into warm water until it will no longer dissolve.

- Mix the two solutions in any proportion that you like. The more deeply colored solutions will produce darker crystals, but it will also be harder to monitor crystal growth.

- Grow a seed crystal using this solution, then tie it to a string and suspend the crystal in the remaining mixture.

- Loosely cover the container with a coffee filter or paper towel. At room temperature (~25°C), the crystal can be grown via slow evaporation for as little time as a few days or as long as a few months.

- To grow a clear crystal over a colored core of this or any other colored alum, simply remove the crystal from the growing solution, allow it to dry, and then re-immerse it in a saturated solution of ordinary alum. Continue growth for as long as desired.

Crystals - a handbook for school teachers

Elizabeth A. Wood, 1972

Written for the Commission on Crystallographic Teaching of the International Union of Crystallography

The IUCr is pleased to make available once again Betty Wood's classic text as an addition to the Teaching Pamphlets series. The original edition was addressed 'To the Teachers of Young Children Everywhere', and in an effort to extend the reach of this text as widely as possible, a number of volunteers have generously given of their time and effort to produce translations in a number of other languages.

Translations

For non-English-language versions, if you do not see the expected alphabet, you may need to set the character encoding for your browser. Suggested settings are listed in square brackets.

- English

- Arabic, translated by Karimat El-Sayed and Boshra Awid [Arabic Windows-1256]

- Czech, translated by Lida Dobiasova [Western ISO-8859-1]

- Dutch, translated by Luc Van Meervelt [Western ISO-8859-1]

- Polish, translated by Zofia Kosturkiewicz [Western ISO-8859-1 or Unicode UTF-8]

- Russian, translated by Elena Boldyreva [Cyrillic Windows-1281]

- Spanish, translated by Juan F. Van der Maelen Uria with Carmen Alvarez-Rua Alvarez, Javier Borge, and Santiago Garcia-Granda [Western ISO-8859-1]