Editorial

Editorial

![Thumbnail [Thumbnail]](https://www.iucr.org/__data/assets/image/0011/157349/thumbnail.png)

Many of us have now returned to our home countries after attending the IUCr Congress in Melbourne. I hope that everyone found it both enjoyable and, even more importantly, scientifically fruitful. Having attended every IUCr Congress since 1966 (apart from the Prague meeting, which I watched remotely), I can look back and think about the value of these big international meetings that we hold every three years. Obviously, they provide an opportunity to learn about new science by listening to the talks and looking at the posters. But it also enables us to meet with each other, sometimes seeing old friends but also making new acquaintances. And often, this leads to new scientific collaborations. This is why the Congresses matter. At the Melbourne conference, in particular, a considerable effort was made to advertise our subject to the general public through a superb talk by Jenny Martin: “How I fell in love with Crystallography and why you should too!” In addition, schoolchildren were invited to learn about crystallography through talks specifically aimed at them with the chance to see and play with several crystal models. Part of this involved everyone helping to construct the largest crystal model ever made (see above). You can read some more about the Congress in an article in this issue by Chris Sumby. I hope to have further details in the next issue of the Newsletter.

![[Fig. 2]](https://www.iucr.org/__data/assets/image/0003/157557/Fig.-2.jpg)

In the last issue, I mentioned the then-upcoming Oxford Hatfest. I am pleased that Marjorie Senechal has written us a report of that meeting where you can see just how much excitement was generated by the discovery of a single shape that could be stacked together, leaving no gaps but also not having periodic symmetry (at least in our three-dimensional world!). While obviously a rather exotic bit of the mathematics of symmetry, one question I would raise is this: are there any actual crystals out there that have this kind of aperiodic structure? Start searching: a possible Nobel Prize may await you!

For crystallographers, it is essential that they learn about the concept of symmetry and how it applies to crystals. The MathCryst Commission of the IUCr performs a valuable service in this regard through holding regular schools in different parts of the world. These are led mainly by Mois Aroyo and Massimo Nespolo together with other instructors. The latest school was held in Nancy and is described here.

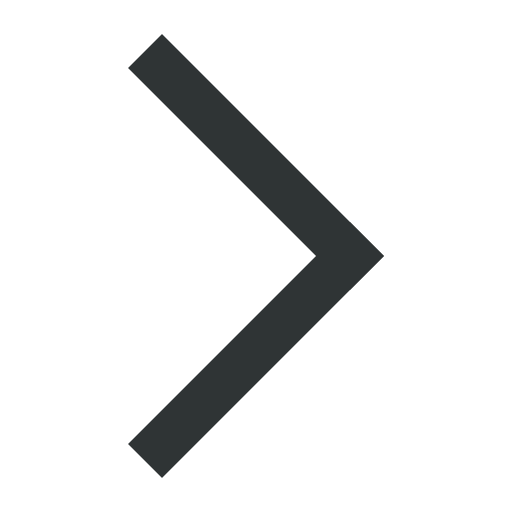

Now, while it is the case that the concept of symmetry lies at the heart of our understanding of crystals and their structures, it should be emphasised that this is a concept that only really applies to a so-called infinite ideal crystal. Such a crystal does not exist, as in reality there are all sorts of defects and disorder always present, plus the crystal surfaces. Nonetheless, an understanding of symmetry is an essential starting point for describing crystal structures and their physical properties. If symmetry were all there were to a crystal, then I think it is fair to say that none of us would exist. Sometimes it is said that “symmetry is death.” This makes sense because true symmetry is by definition, unchanging and frozen, and therefore has nothing to say about any progress or development. It is the breaks in symmetry that are responsible for the world we live in. Every new discovery can be thought of as symmetry breaking. But to understand the breaks, one needs first to understand symmetry itself. I often illustrate this idea by playing some awful music to my students. I start with a set of repeating notes, i.e. highly symmetric and periodic, showing that such “music” soon becomes boring (see upper line in the figure).

![[Fig. 1]](https://www.iucr.org/__data/assets/image/0003/157350/Fig.-1.jpg)

However, if, along the way, we introduce two or three different notes (lower line), this immediately captures our attention. Admittedly this is still not great music but it does serve to illustrate the effect of symmetry breaking. So, symmetry on its own is boring! I often upset the “crystal healing community” by pointing out that crystals are the “deadest” things in the universe! Now, having said that, symmetry does mean that crystals are very pretty and in this vein Istvan and Magdolna Hargittai have written an entertaining article entitled “Crystals humanized”.

Another way by which the beauty of crystallography is brought into the public square is through the holding of crystal growing competitions. Here, schoolchildren are given the necessary chemical agents and learn how to grow crystals from solution. The best crystals are then judged for quality and size. In this issue, we have reports from Canada and the USA of the latest crystal growing competitions.

As ever, as Editor I have the sad task of reporting the deaths of fellow crystallographers. Bruce Forsyth (RAL) and John White (ANU, Canberra) were well known for their work in neutron scattering. S. K. Sikka (BARC) was an eminent high-pressure physicist. Michael James and Raimond Ravelli were well known structural biologists working in Edmonton and Grenoble, respectively. And then very recently we heard of the death of Henk Schenk, President of the IUCr from 1999 to 2002. I hope we shall have an obituary for him in the next issue of the Newsletter. I well remember his lectures on the crystallography of chocolate!

Copyright © - All Rights Reserved - International Union of Crystallography